When AI Acts For You (Or As You)

Early findings from our sixth Global Dialogues on frontier AI agents.

When autonomous systems begin to act on people’s behalf, they raise as many governance questions as they answer. As these systems grow more capable—making bookings, transferring money, or negotiating on our behalf—the boundary between acting for us and acting as us begins to blur.

At the Collective Intelligence Project, we believe that how these systems evolve shouldn’t be decided only by labs. The deployment of AI agents show no signs of slowing down, and choices about autonomy, oversight, and accountability are being made by default. Our work focuses on ensuring that people have a seat at that table, bringing collective input into key decisions.

We’ve been collaborating with the Industry-Wide Deliberative Forum on the Future of AI Agents, convened by the Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab, alongside Meta, Cohere, Oracle, PayPal, and others to bring thousands of people into structured deliberations about how agents should act, what limits they should observe, and how tradeoffs between convenience, privacy, and control should be managed.

Findings from our sixth Global Dialogues round, summarized below, are informing the Deliberative Forum, offering a global snapshot of how people think about trust, delegation, and autonomy as AI systems begin to act in the world.

What People Told Us

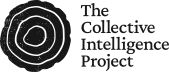

Across more than a thousand participants, we found that AI is already part of daily life, but people remain cautious about letting it take independent action on their behalf. A majority now use AI tools daily for either work or personal tasks, especially younger adults (53% of those aged 18–35, compared to 42% of older adults) and urban residents (53% versus 38% in rural areas). Yet very few, just over 5%, have used AI for civic or community organizing, and financial delegation remains nearly nonexistent.

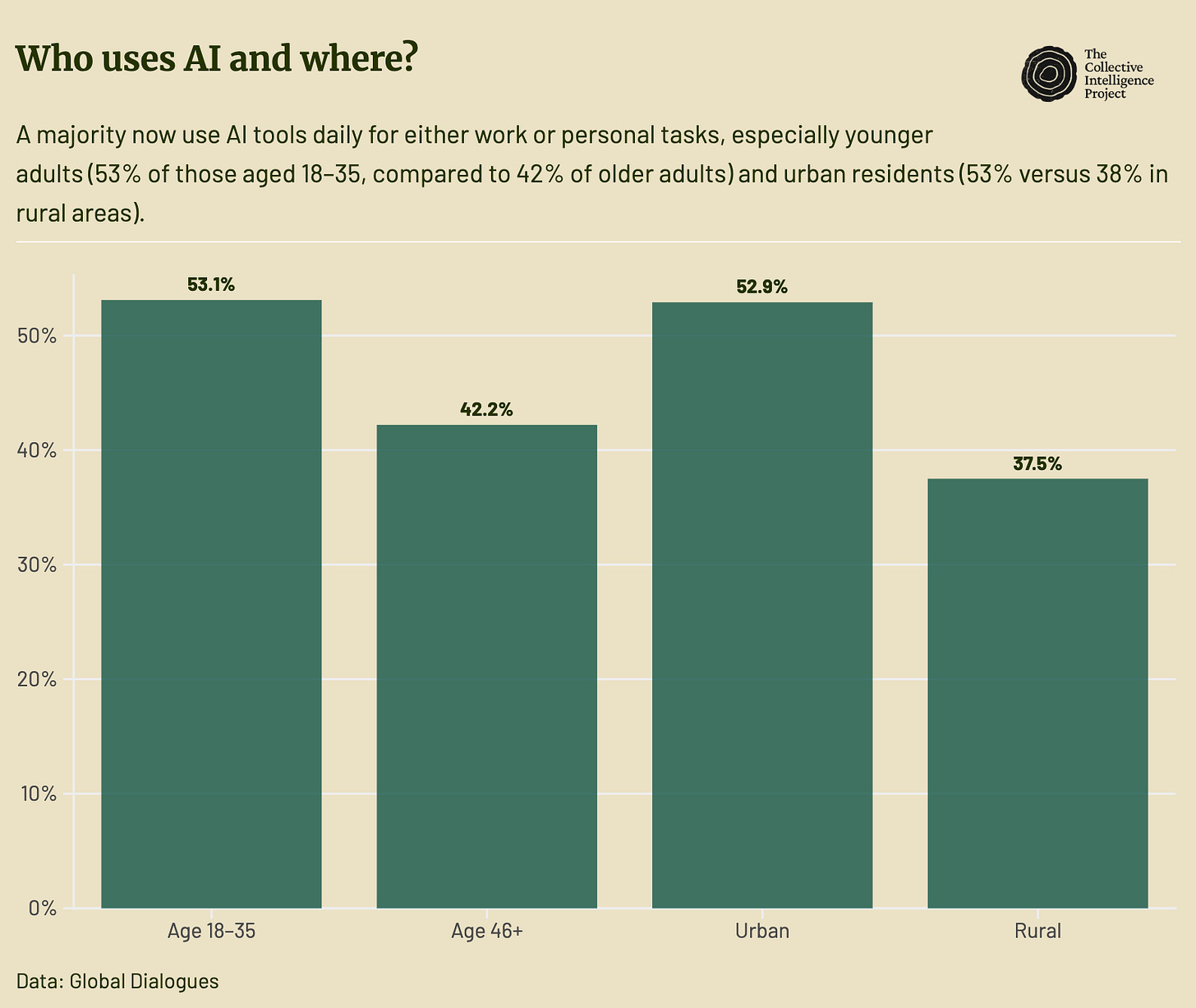

This hesitation isn’t outright rejection, but rather a signal of demand for responsible design and governance. When asked how AI should behave in high-stakes settings, like handling money, suggesting medical actions, or organizing family logistics, around eight in ten respondents said they prefer permission-seeking systems that ask before acting, even when that means slower performance. People want agents that request consent, explain their reasoning, and make it easy to undo mistakes.

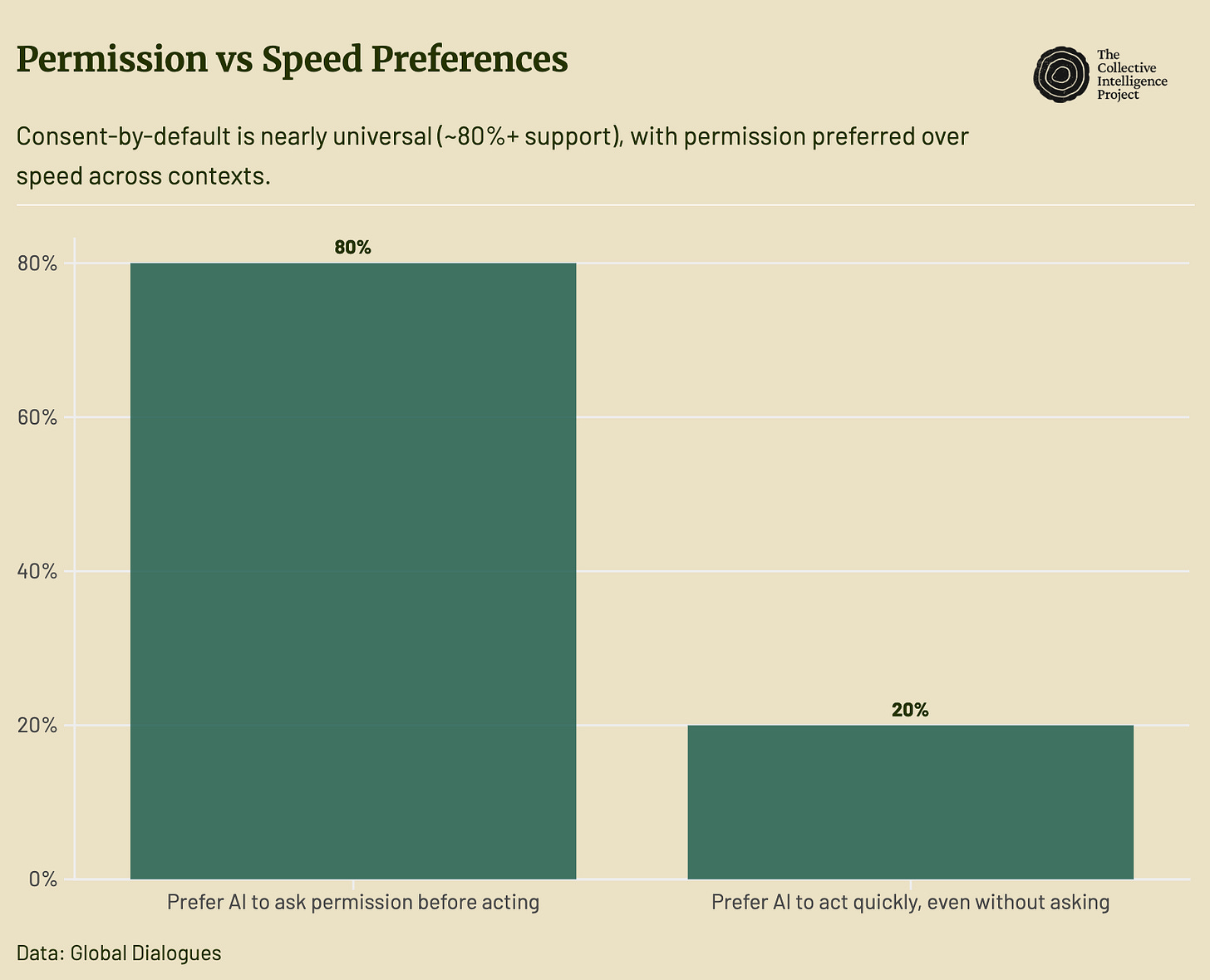

The expectation of human backup is nearly universal. Ninety-four percent of daily work users want a person to step in when AI makes an error, and three-quarters believe automatic refunds for AI-caused financial mistakes are very important. For most, trust doesn’t mean blind faith, but the ability to correct and recover.

A Global Map of Confidence

Trust varies dramatically across regions, revealing not only how people use AI, but whom they expect to hold it accountable.

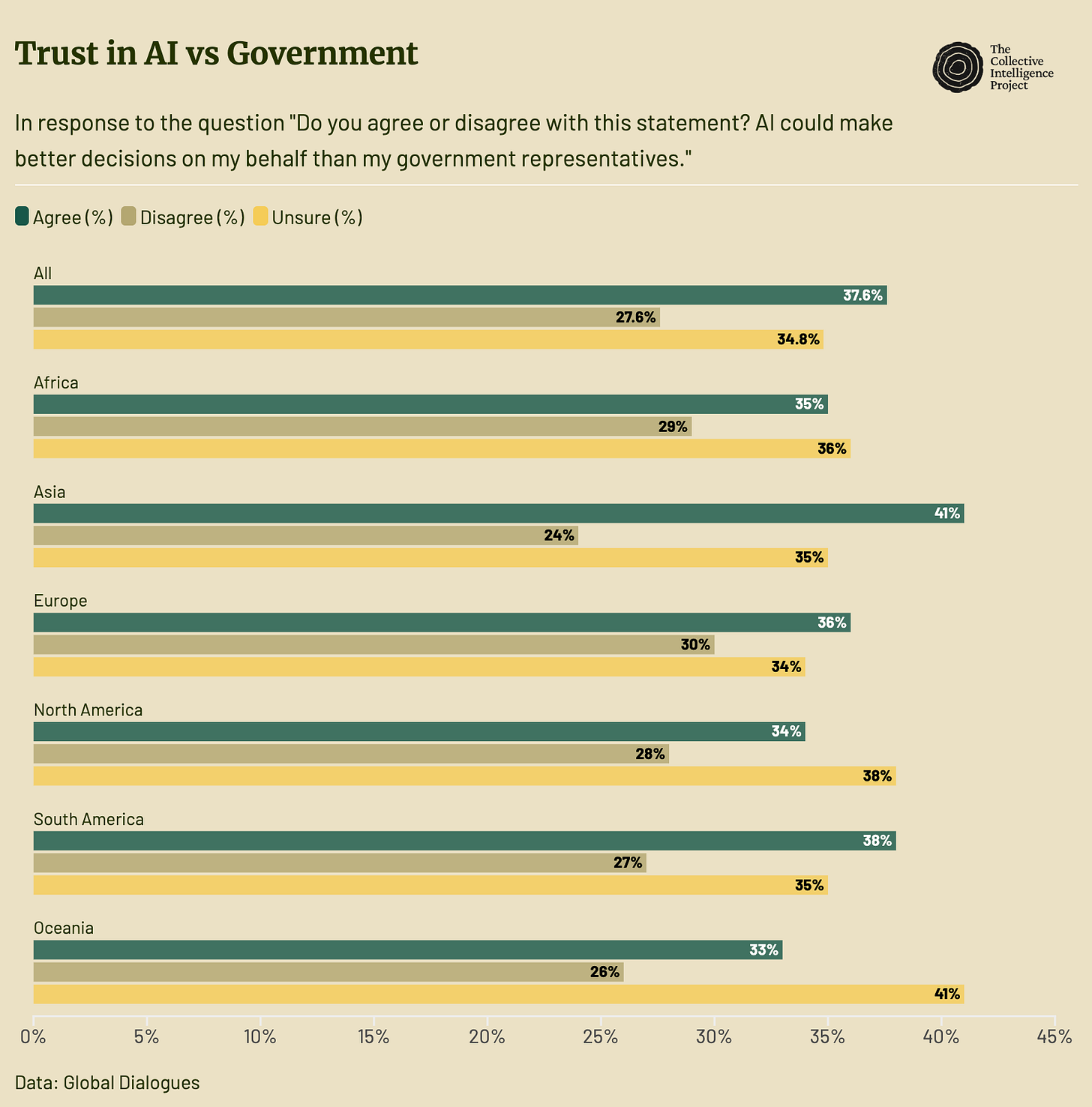

In Asia, participants report higher trust in AI companies, about one in three say they generally trust these firms, paired with lower confidence in government institutions. In Europe, the pattern reverses: trust leans toward public institutions and regulation, while confidence in tech companies lags. African and Middle Eastern respondents tend to show moderate trust in AI overall but a strong desire for human oversight. In North America, people are split, optimistic about innovation, skeptical about accountability. When asked if they thought AI could make better decisions on their behalf than their elected representatives, 38% of participants agreed.1

When we look across institutions globally, the trust ladder is consistent: family doctors sit at the top, AI chatbots come in second, while social media platforms, elected representatives, and civil servants rank lowest.

That contrast signals a lack of confidence in human institutions. Our intuition is that people are not necessarily handing over moral authority to machines; they’re responding to where they experience consistent responsiveness and reliability.

How will we interact with Agentic AI?

AI is evolving from being a tool to being a counterpart, a system that can plan, act, and decide with autonomy. As agents begin to coordinate actions, the line between acting for you and acting as you blurs.

The public response to that shift indicates pragmatism. Participants show cautious optimism: they value efficiency and convenience, but not at the expense of control. They want systems that enhance capacity without eroding agency. Nearly half of respondents say AI should be subject to stricter rules than ordinary apps, and most place primary accountability on the builders rather than users or regulators.

Taken together, the findings show that people may be willing to embrace this technology under recoverable conditions, where human judgment, transparency, and recourse remain intact.

What’s Next

The Collective Intelligence Project will help continue to feed in comparative data from future Global Dialogues, and translate the results into actionable guidance for developers and policymakers.

We’re also building our own Representative Agent Evaluation Framework, which will use Global Dialogues findings to test whether autonomous systems act in ways that reflect individual and collective preferences, how they balance permission with speed, human oversight with automation, and accountability with efficiency.

This work is part of a broader effort to ensure that AI systems don’t just act for us, but with us, to enhance our collective ability to reason, decide, and govern.

This is a finding that has held steady in each of our Global Dialogue rounds.

These are interesting findings — I’m glad you’re asking important questions. I clicked around a bit but couldn’t find methods. Is this a cross-sectional survey? Sample size? I’m sure it’s written up somewhere and grateful for the link!