How does the world feel about the possibility of understanding other species?

Findings from our Global Dialogue on AI and interspecies communication.

The fifth round of our Global Dialogues was conducted in partnership with the Earth Species Project (ESP), a non-profit at the forefront of developing AI for interspecies understanding. As a research organization specializing in collective intelligence and democratic governance, we worked with ESP to conduct this first-of-its-kind global dialogue, involving 1,057 participants from 67 countries. Our shared goal was to understand public hopes and concerns before the technology becomes widespread, ensuring that its development is guided by public input rather than reacting to it after the fact.

We’re also releasing the dataset for anyone to explore the findings and build upon it for their own research. The data was collected using our Global Dialogues methodology, in which a globally broad and inclusive sample of people from around the world provided input into questions and scenarios, and were prompted to respond to and comment on the answers given by other respondents. This process allows us to create a dialogue among the participants, eliciting richer responses and feedback. For details on the methodology see here.

Key Findings

Seven in ten people want to know what animals are thinking. This prospect generates significant curiosity (60.5%) and hope (47.7%) across diverse populations, from urban centers to rural communities and across six major world religions. Overall, our global sample feels that this is a good use of technology. 45.2% of all participants believe AI for interspecies understanding is a good use of technology; 11 times higher than those who reject it.

While the public expresses enthusiasm for AI-powered animal communication, this optimism is tempered by significant concerns – not about the technology itself, but about human misuse. Our research shows the primary perceived risk concerns how people will leverage the ability to understand the communication of other species. Respondents worry most about humans exploiting, manipulating, or harming animals for commercial gain or selfish motives. The core fear is that the technology will work exactly as intended by the wrong people, enabling harm rather than fostering understanding.

Regulation as the baseline expectation

The response to this concern is clear: 84.9% of the global public agrees that companies profiting from animals should face strict rules on how they use AI to understand them. Majorities support prohibiting specific uses:

68.3% would ban deception for commercial gain

62.7% would ban threats or inciting violence

62.5% would ban commands that override natural instincts for human benefit

This suggests that regulations are wanted before any such technology could be deployed at scale.

The AI optimist/pessimist divide appears again

How people feel about AI, in general, relates to their views on interspecies communication.

AI optimists view it as progress: 56.8% call it a good use of technology, and 63.4% trust AI to interpret animal communication without distortion.

AI pessimists are less convinced: only 34.3% see it as a good use of technology, and just 29.6% trust AI’s objectivity.

The split also reflects different worldviews about human-animal relationships. AI optimists are more likely to see humans as fundamentally superior to animals (71.7% vs. 51.8% of pessimists). In contrast, AI pessimists are more likely to hold an egalitarian view (47.3% believe in equality vs. 25.5% of optimists).

It’s too early to draw definitive conclusions, but it suggests that there will be significant cultural and political concerns to address regarding the deployment of AI technologies.

Cultural divisions may have implications for regulation

When asked how understanding animal communication might transform our ethical responsibilities, one response generated a massive 78-point divergence between countries: “Humans can barely tolerate someone with slightly different skin color, let alone some entirely different species.”

The agreement rates on this statement were 94% in Pakistan and 16% in Canada.

These divisions represent fundamentally different starting assumptions about human nature and the feasibility of interspecies ethics. This finding indicates that a single global policy framework that works in one region of the world may be incomprehensible or ineffective in another.

Ownership in the more-than-human world

Just over half of our population (57%) believe that either the animal or the community protecting those animals should own the recording. However, the question of data ownership is another area where global consensus didn’t exist, although the divergences themselves are of key interest. When asked who should own a recording of animal communication, responses were divided:

39.7% say the community protecting those animals.

32.8% say the human who recorded it.

17.3% say the animals themselves should own it.

The view that an animal should own its communication data, held by nearly one in six people, is not a fringe position. It is a significant minority view that will create novel legal and ethical conflicts as the technology develops.

Implications for legal rights

These new technologies open up legal questions. When asked if an animal should have the right to a representative (such as a lawyer) to defend its rights and protections, if AI could give us amplified insights into their needs, 42.6% said yes.

We asked our sample about the most appropriate approach for protecting animals. Of the people who chose “Animals should be given legal status as a recognized creature with a voice, similar to the rights of a minor child” we found some of the highest consensus statements when we asked people to explain why they chose this option:

“Making animals legal creatures provides official protection and provides a voice regarding matters influencing them. This is not empathy, it turns to enforceable justice, where their interests are legally guarded”

65% min agreement

“Since animals can speak, they have inherent rights and should be protected.”

62% min agreement

“They would have more rights because they would be able to be understood.”

62% min agreement

“The people are guided by rights in constitution and rule of law so having legal rights protect the animals too”

61% min agreement

What people actually want: relationships before rights

Despite openness to new legal frameworks, when given three options for protecting animals, the public overwhelmingly chose a relational approach over a legalistic one:

63.2% prefer building ongoing relationships and communication.

25.0% prefer including all voices in shared decision-making.

11.8% prefer granting legal rights and representation.

The most agreed-upon response, with 72% agreement, was: “Building relationships with animals might be the best outcome of this technology which would not harm the interests of animals and will make human-animal understanding better.” The data shows a clear public preference for connection and listening over litigation and enforcement.

A more comprehensive approach is also highly appealing. We asked people to respond to the following scenario:

“Consider a scenario where societies of the future are governed by AI systems that integrate data from both human and non-human sources (such as environmental sensors and wildlife communication networks) to guide community decisions (e.g., urban planning, conservation zones). How appealing is this vision of an ecocentric, integrated society?”

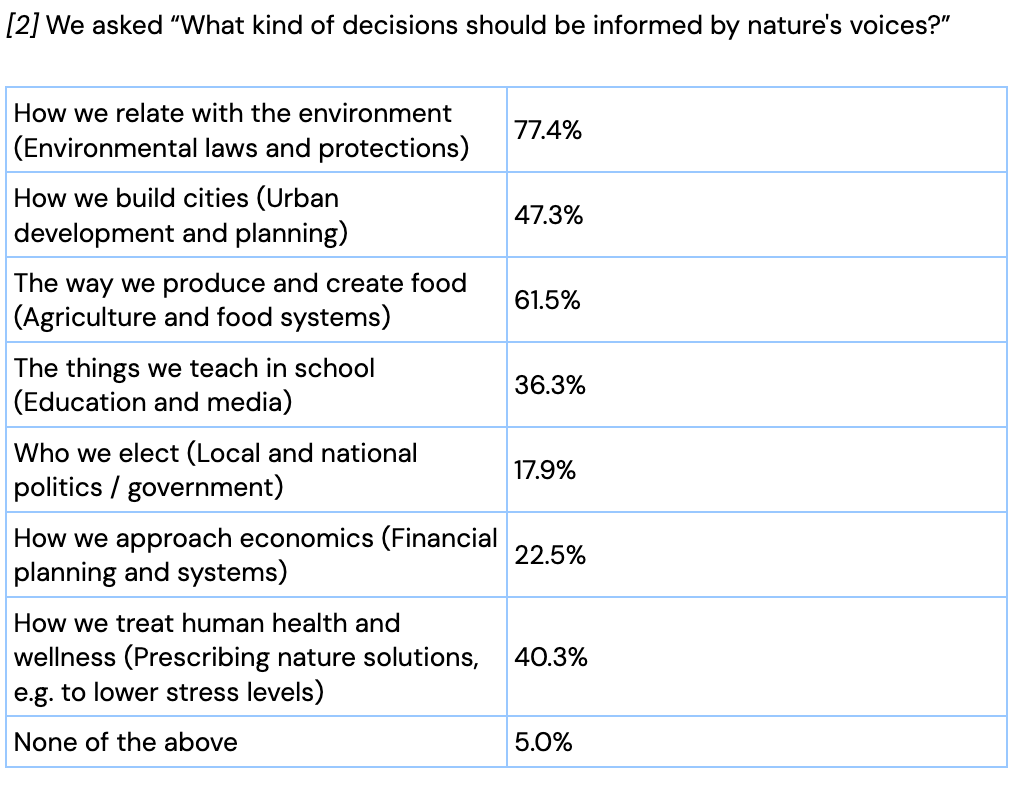

79.2% of the global public finds this vision of AI systems integrating human and non-human data for community decisions at least somewhat or very appealing.1 We also asked “What kind of decisions should be informed by nature’s voices?” and 77.4% think environmental laws and protections should be informed by input from nature (Agriculture and food systems: 61.5%, Urban development and planning: 47.3%, Human health and wellness: 40.3%, Education and media: 36.3%) 2

When asked what the most profound change might be if animal and ecosystem voices were taken seriously in our laws and systems, the consensus centered on an ecocentric shift, yielding some of the highest consensus responses:

“Our ecological environment will no longer be based primarily on human suitability, but will become more comprehensive”

61% min agreement

“Society world wide would be more environmentally conscious and have more broader perspective as a society.”

61% min agreement

“Maybe a more ecocentric world and protecting plus prioritizing other beings as well”

61% min agreement

What this means for AI governance

These data demonstrate a public ready to engage with AI’s expanding capabilities, but on clear terms. For developers and policymakers, those terms include:

Strict boundaries on commercial use. Companies developing AI for understanding interspecies communication should expect a public demand for regulation before, not after, deployment.

Geographic and cultural customization. A single, homogeneous global policy is likely to fail given the large divergence in ethical frameworks between regions.

Focus on human behavior, not just technical safety. Risk models for this technology must center on preventing human misuse, not simply on AI malfunction.

This tension is best captured in public responses to the question, “How might advancements in understanding animal languages transform our ethical responsibilities towards non-human species?”:

“I think humans are already not ethical, they do what they feel best for them... more technology to understand animals will only lead to more misuse in my opinion.”

65% minimum agreement, particularly high in: Eastern Africa (83%), Central America (81%), Kenya (84%), Morocco (82%)

However, the public also sees its potential to enforce accountability and drive protective action:

“They could make us feel responsible for damage to ecosystems.”

60% minimum agreement

“We would have to drastically increase protection laws.”

60% minimum agreement

Ultimately, a significant portion of the public believes in a path toward greater empathy and a fundamental shift in posture:

“It will increase empathy... It will make us care more about the environment, about protecting the animals... proper and responsible governmental intervention will be crucial.”

59% minimum agreement

“We should listen to them more than we do now.”

59% minimum agreement

Anticipation of novel legal conflicts. When nearly one in five people believe animals should own their communication data, institutions must prepare for property rights questions that current legal systems cannot address.

Understanding public input on emerging AI applications

This Global Dialogue demonstrates how public perspectives on AI diverge across cultures, demographics, and prior attitudes toward technology. The patterns we see here mirror what we’ve found in our consciousness attribution research: people’s general stance toward AI shapes how they evaluate specific applications. For AI labs and policymakers, this means research must account for:

How worldviews about human-animal relationships and technology inform each other. Future research is needed to determine causality and correlation.

Where cultural divides will create policy friction.

What specific forms of human exploitation and misuse the public fears most.

We’re using Global Dialogues to map these patterns as AI capabilities expand into new domains. Our next dialogues are exploring themes such as the impact of AI and mental health (mania, delusional disorder and reality distortion), digital sentience, and the economic restructuring of society in a post-AI world.

We asked “Consider a scenario where societies of the future are governed by AI systems that integrate data from both human and non-human sources (such as environmental sensors and wildlife communication networks) to guide community decisions (e.g., urban planning, conservation zones). How appealing is this vision of an ecocentric, integrated society?”

Somewhat appealing: 59.2%, Very appealing: 20.0%

This is amazing. It reminds me of Bruno Latour's 'Facing Gaia'