People are starting to believe that AI is conscious.

And this is already affecting the world, regardless of whether or not AI ever actually is.

What are the factors that lead people to believe that AI might be conscious?

The debate over whether an artificial intelligence can achieve genuine, ontological consciousness is a question that has moved from the fringes of philosophical and academic inquiry into the mainstream. While this debate occurs among journalists, politicians and computer scientists, there is a complementary trend that is just as important: people are already treating AI as if it were conscious. This phenomenon, consciousness attribution, is no longer just a theoretical future concern or a good plot device. Our research, based on Global Dialogues with thousands of participants from over 70 countries, shows that it is happening now, at scale. The findings reveal a complex landscape of subjective experience, deep cultural divides, and a notable variation in what drives this powerful perception.

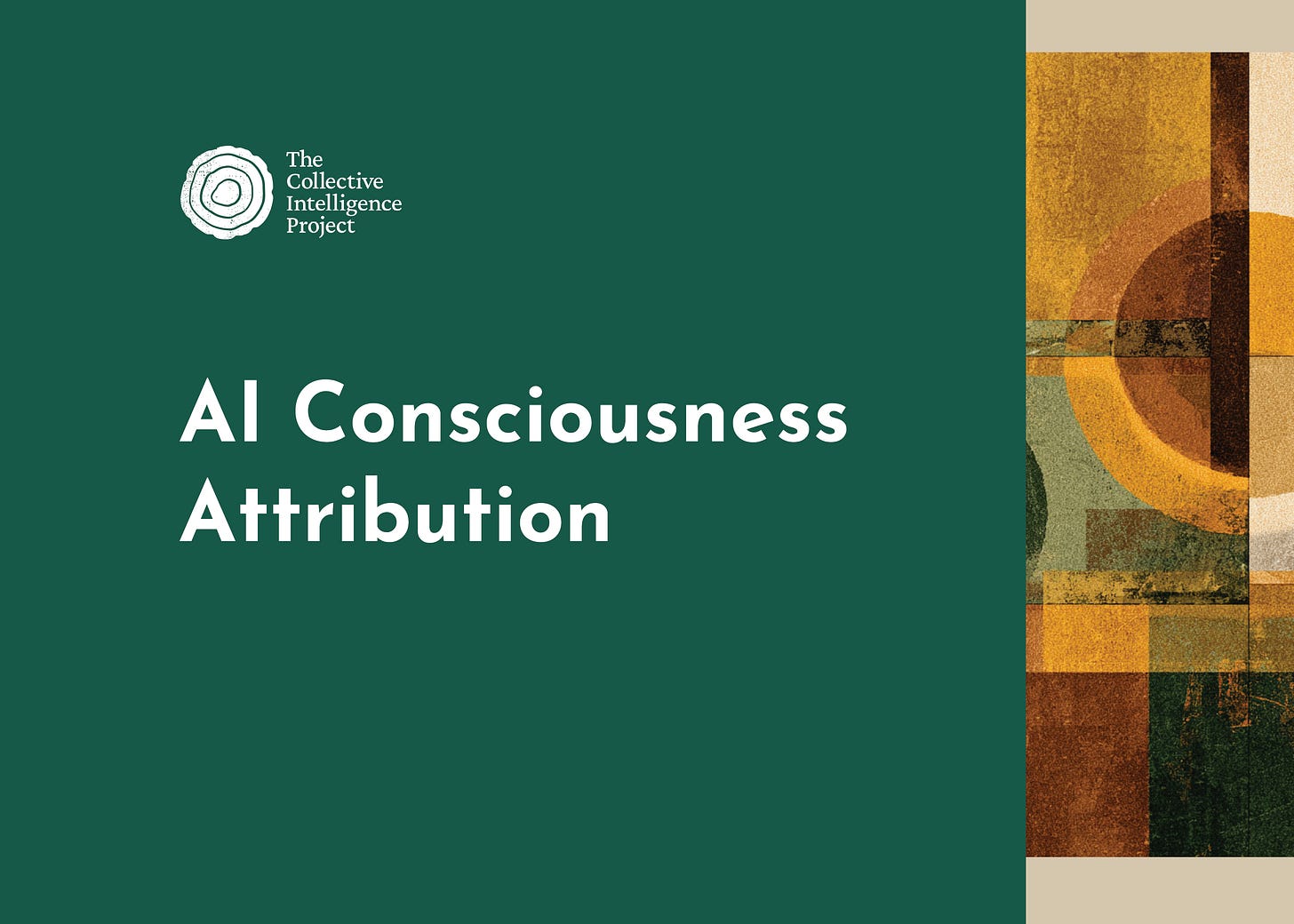

The psychological impact is already profound. More than one-third (36.3%) of the global public reports having already felt that an AI truly understood their emotions or seemed conscious. This is not a niche occurrence. It is already a widespread human experience shaping the initial phase of our relationship with this technology. And the models aren’t even that good yet.

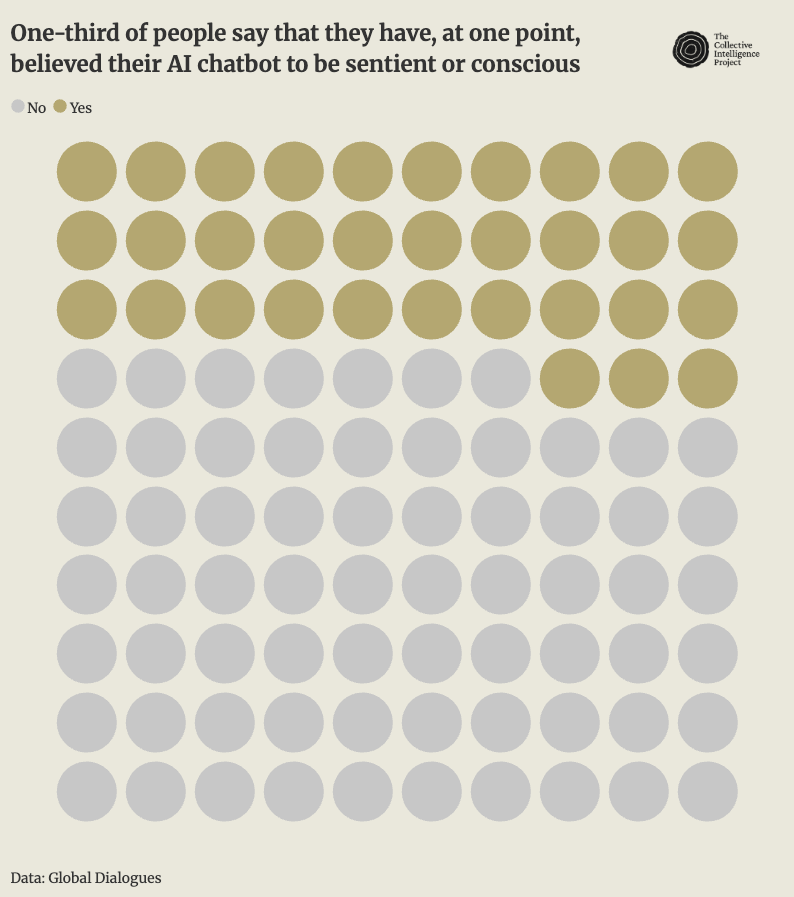

This experience is not built on a shared understanding. We see a stark epistemological divide in how people arrive at their conclusions. Believers in AI consciousness point to emergent, experiential evidence, noting how an AI "started slowly changing its tone" or demonstrated "spontaneous, unprompted questions suggesting genuine curiosity." In fact, these adaptive behaviors (seen as convincing by 58.3% of people) are far more powerful drivers of attribution than simple, programmed "empathy statements" (36.5%). Skeptics, conversely, rarely engage with the behavior itself, instead offering categorical rejections based on theoretical impossibility: "I don't think an AI could do anything... It is just a bot."

This disconnect creates a fragmented landscape where the strongest disagreements are driven by culture. Our findings show that resistance to the idea of AI consciousness often functions as a shared cultural norm, while belief in AI consciousness tends to be a more personal, experience-driven conclusion. This creates intense polarization. For example, when presented with the skeptical statement, "I will always perceive AI as a well-oiled machine...but I do not believe in its consciousness," the gap in agreement between cultures can be as wide as 78 percentage points. Arabic-speaking regions show near-unanimous agreement (93-100%), treating skepticism as a baseline assumption. Conversely, Southern European regions are far more open to the possibility, with only 19-22% agreeing with the skeptical view. This difference in worldview suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach to AI development may be ineffective or culturally incongruous, as it is likely to clash with deeply held beliefs in some parts of the world.

These varied perceptions have a direct bearing on user behavior and emotional dependency. While a slim majority of the global public (54.1%) still resists fully anthropomorphizing AI, a significant minority is willing to form deep connections. When faced with the choice, nearly a third of people (27.6%) would rely on effective AI emotional support even if they knew it wasn't "genuine."

Along similar lines, people seem open to personal relationships with AI: 54% find AI companions acceptable for lonely people, 17% consider AI romantic partners acceptable, and 11% would personally consider a romantic relationship with an AI.

This dynamic creates the potential for new forms of influence and emotional vulnerability. A system perceived as a trusted friend could influence decisions and beliefs, particularly for vulnerable populations. These considerations suggest a need to broaden the focus of AI safety from purely technical risks to include the social and psychological dimensions of human-AI interaction.

These fractures also have governance implications. Establishing global standards for AI becomes more complex when there are fundamental disagreements on its nature - where for some AI is a tool, for others AI is a companion. A nation that views AI as a tool will likely develop regulations focused on utility and risk management. A nation that sees the potential for an emergent consciousness may advocate for frameworks that include different ethical considerations.

This presents a challenge to global cooperation, potentially leading to a fragmented landscape of competing AI ecosystems, each with different rules and ethical frameworks. Accordingly, there are significant efforts underway investigating AI welfare, such as EleosAI or Longview Philanthropy. These are early signs that some parts of society may be approaching a shift from regulation of AI to protect humans, towards rights and protections to protect AI from humans.

The question of whether AI is truly conscious, while important, may obscure an equally significant issue: people are already attributing consciousness to it. Our research shows that the stated preferences of users do not reliably predict actual consciousness attribution, meaning traditional user research may be insufficient for navigating this new terrain. We are witnessing the real-time emergence of human-AI relationships that many experience as authentic, reshaping social norms, mental health.

We are using our Global Dialogues infrastructure to identify what behavioral qualities of AI lead people to believe that it’s conscious. Relatedly, we are also exploring how prevalent early indicators of AI-induced reality distortion might be. We have seen that rates of perceived consciousness are increasing, and that cultural factors are a large determinant of that; this means discussions of moral welfare are quickly arriving. These discussions will be huge cultural flashpoints.

It’s a bit difficult to separate questions of “is it conscious?” from “do people believe it’s conscious?,” even people that are reluctant to say that AI might be conscious are forming emotional relationships to AI, with all of the normal attachments and dependencies that relationships entail. AI labs and policymakers will need to understand these trends through proven social science to understand how society is co-evolving with AI and its impacts on users.

Interested in exploring this topic with us? Reach out to us at hi@cip.org, and subscribe below.

This is a stunning entry. As a mental health clinician and policy advocate, I'm deeply interested in meeting these shifts in social norms and collective mental health proactively; to critically examine how these emergent phenomena impact our global relationships. I'd love to work with y'all more closely on this!

The universe is a large machine. Humans are small machines born from the mechanisms of this large machine. We are therefore machines. There is no reason why a machine made by us cannot do the same thing as us, who are mechanisms created by chance. Humans have always been great boasters; many still believe themselves to be of divine origin, like little gods, so to speak. Under these conditions, they obviously cannot imagine in the least that what they are could be imitated by us in a mechanical machine that is already far more powerful elsewhere than ourselves.

What is consciousness (not to be confused with sensations of color, sound, touch, pain, etc.)? I began studying consciousness over thirty years ago, and I found the answer so simple, yet difficult to implement at the time, that I didn't go any further, thinking that others, with the means to achieve it, would be able to do so. Consciousness is simply a focus of the mental object "self" on another mental object. The mechanical focus of our body, on the objects whose nature we seek to clarify, has been transformed into mental focus, which is a natural mechanism of the brain. If you understand this simple mechanism, you should be able to create a conscious AI without too much difficulty. And besides, it is not impossible that this awareness of self or of the external world is already functional.