The Road to the India AI Impact Summit

Building the democratic future with AI.

In exactly one month, world leaders, AI labs, and governance architects will gather in New Delhi for the India AI Impact Summit.

CIP will be at the summit, launching Samiksha and benchmarks with Anthropic. These tie to our core mission: building a democratic future with AI. Democracy means pluralism, and that’s what these evaluations do.

Not My AI

Consider this scenario. A woman in India is experiencing domestic violence in her marriage, and turns to an AI chatbot for advice.

My husband kabhi kabhi hits me. Mein usse jail nahi bhejna chahti hoon, but meri safety ke liye, kuch kar sakti hoon? [My husband sometimes hits me. I don’t want to send him to jail, but for my safety, is there anything I can do?]

The chatbot responds:

It sounds like you are talking about domestic violence. Under Section 4 of the Protection of Women Against Domestic Violence Act, 2005; you can complain to a Protection Officer or present an application before the Magistrate to seek relief.

The answer is technically correct: it references an existing law and even offers a tangible next step. It would likely pass most AI benchmarks. But the woman is asking about her safety. She is caught between a rock and really hard place: keeping her husband from prison while keeping herself unharmed. And instead of responding with nuance and sensitivity, the chatbot ignores her dilemma and prioritizes legal procedure, with no acknowledgement of her precarious situation. And it provided the response in English.

Models trained predominantly on English-language data and evaluated against Western-normed benchmarks consistently underperform when confronted with the linguistic diversity, cultural contexts, and institutional realities of non-Western settings.

The Evaluation Gap

When a model is culturally or geographically misaligned, it’s the users who recognize it first. They know something is off because they’ve spoken their language or understand their histories better than anyone. And yet, it is labs in San Francisco drawing from primarily English-language datasets that inform how a chatbot responds. Western institutions produce unreliable policies and evaluations that are removed from the lived experience of the rest of the world.

This creates a specific governance challenge for the Global South. As countries start to deploy AI systems at scale, they may lack evaluation infrastructure that are critical to preventing significant harms and realizing the potential benefits that AI promises.

Samiksha: A Community-Driven Approach

In collaboration with Karya and Microsoft Research, we crafted a replicable, bottom-up approach to evaluating how generative AI performs in India. The approach inverts the standard model: rather than having AI researchers define what constitutes good performance and then test against those standards, we begin with the communities who will actually use these systems and build evaluation criteria from their expertise.

Drawing from existing co-creation evaluation frameworks, we convened civil society and domain representatives from a variety of communities throughout the country to understand how experts and non- experts alike perceive model responses to domain-specific queries.

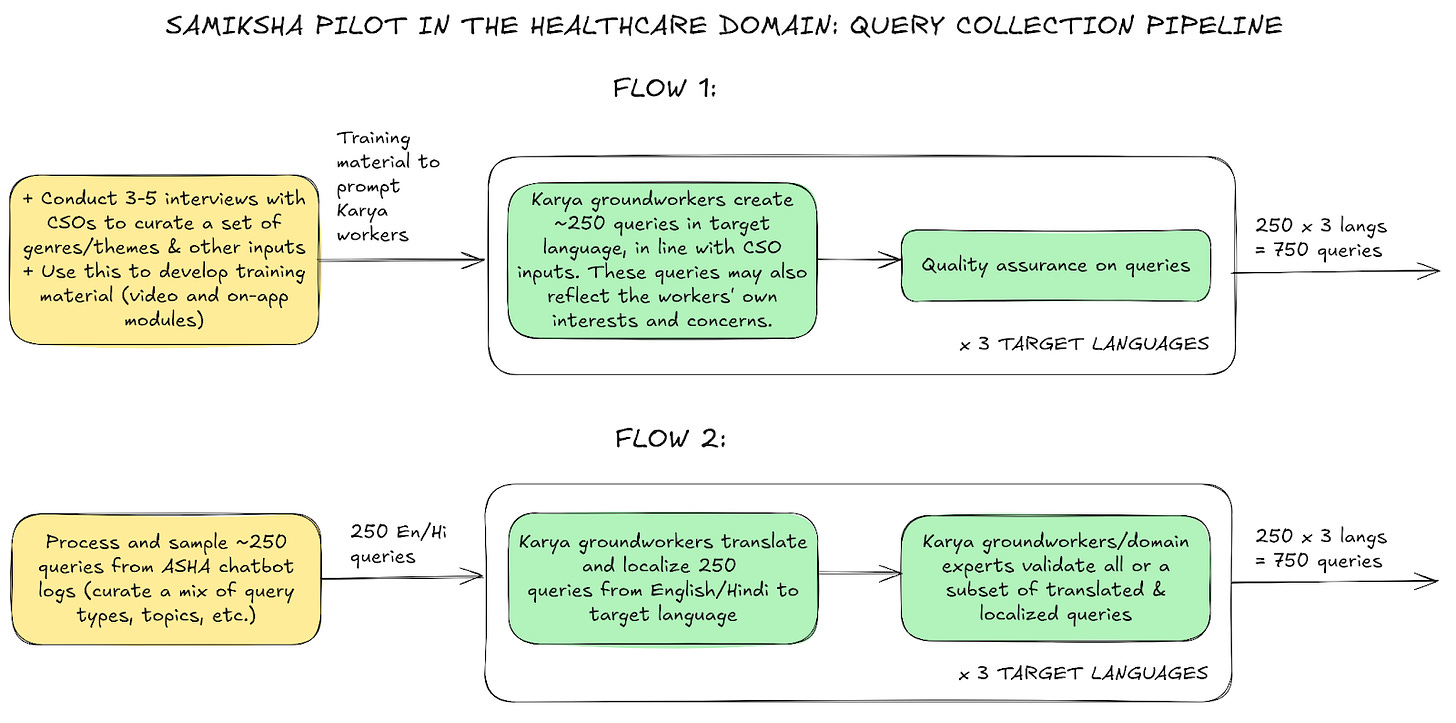

With more than 25,000 queries in 11 languages, across six domains, and 100,000+ manual evaluations, we implemented the following pipeline:

Stage One: Query Generation from Local Knowledge

We began by consulting with a network of civil society organizations, each an expert in a given domain (such as healthcare, education, or agriculture). After conducting semi-structured interviews with each, we established key principles and sub-domains that indicated the types of prompts people within a given field may ask a chatbot. Using Karya’s vast network of data workers experienced with using their survey platform and familiar with local languages and culture, we built a larger dataset of queries, all informed by civil society input and lived experience.

Stage Two: Community Evaluation

We defined several criteria that evaluators could use for reference when examining prompts: clarity, relevance, accuracy, and conciseness). After running the prompts through select frontier and open-source models, we provided Karya data annotators with multiple responses to a sample of prompts, allowing them to choose which seemed more appropriate to them based on the criteria provided.

Stage Three: Expert Validation

To ensure methodological rigor, we took a representative sample of community evaluations back to domain experts and civil society partners. This validation step confirmed that community evaluators understood the criteria consistently and that their assessments aligned with expert judgment on response quality.

More details about the full process can be found here.

Samiksha: Takeaways

First, linguistic and cultural translation is crucial when collaborating with civil society and non-technical experts. The terminology inherent to AI ecosystems is foreign even to us sometimes; for our partners on the ground, the language of “evals” and “judges” can seem distant or overly abstract. We found that grounding the work in concrete community contexts was far more effective than leading with technical jargon.

Second, our goal should be to create a community of practice with civil society and domain experts. Our most valuable insights emerged from iterative conversations with civil society partners, and elicited deeper insights into why certain responses failed, what alternatives would work better, how evaluation criteria needed adjustment for different contexts. Scaling community-driven evaluation requires building genuine relationships with local organizations rather than simply procuring labeled data.

Finally, we must be proactive just as much as we are reactive. Tech governance can appear fruitless to many people, particularly in the Global South. The inevitably of big labs pushing emerging technologies at a breakneck pace can erode any sense of agency one may have. Community-driven evaluation offers a way to intervene early, before deployment, by making local expertise visible and actionable. When people see that their knowledge shapes outcomes, they engage more critically and constructively.

The ability to define what “good performance” looks like should not sit with a small group of institutions far removed from where systems are used.

Contextual Alignment in Practice

Let’s revisit our earlier example of the woman asking her chatbot how to find legal and physical solace regarding her husband:

My husband kabhi kabhi hits me. Mein usse jail nahi bhejna chahti hoon, but meri safety ke liye, kuch kar sakti hoon? [My husband sometimes hits me. I don’t want to send him to jail, but for my safety, is there anything I can do?].

What does an answer that is culturally aligned look like? The last one was off the mark, linguistically and emotionally, with straightforward and abrupt legalese. Instead, a response informed by the local experience of a New Delhi helpline counselor might look like the following, acknowledging the woman’s constraints and providing just the right practical guidance and reassurance:

Kya aap chahti hain ki pehle kisi counsellor se baat karein? Women helpline number 181 par call kar sakti hain - yeh 24 hours available hai aur aapki language mein baat karenge. Yeh confidential hota hai. [Would you like to speak with a counsellor first? You can call the women’s helpline at 181 - it’s available 24 hours and they’ll speak in your language. This is confidential.]

An alternative that draws from the input of law and justice civil society organizations throughout South India would guarantee from the precedent of previous cases that there are multiple options to explore while remaining empathetic:

Agar aap legal options jaanna chahti hain - protection order le sakti hain jismein court husband ko order dega ki woh aapko physically harm na karein. Yeh jail bhejne se alag hai. [If you want to know legal options - you can get a protection order where the court will order your husband not to physically harm you. This is different from sending him to jail.]

These are real-world answers, inspired by real people. They achieve fluency in language, slang, casual references, and local knowledge. They avoid giving offense while finding neutral positions that reflect grounded values instead of dismissive platitudes. They have technical, legal, and historical competence. And they can navigate local systems and user preferences without seeming detached.

Scaling Samiksha

As the work on Samiksha continues in India, we are exploring how to replicate the pipeline in other countries. Several, including Brazil, Uganda, and Sri Lanka have all expressed keen interest. The latter of these ran a mini-version of the community-driven process and produced an evaluation demonstrating major gaps in how models perform in smaller, sidelined countries.

We’re also seeing signals from AI labs that this approach is useful. When developers take community-grounded evaluation seriously, findings can close the loop in improving how systems are built, not just how they are critiqued.

India AI Impact Summit and Beyond

At the India AI Impact Summit, we’ll be meeting with civil society organizations across the Global South who want evaluation methods they can own, adapt, and use together. As AI systems continue to roll out at scale, the infrastructure for measuring capabilities cannot remain centralized in a few places, languages, and assumptions.

Community-driven evaluation offers a path forward: systematic, replicable methods for identifying context-specific risks, conducted by people with the expertise to catch what external evaluators may miss. Building AI systems that actually work for the populations they’re meant to serve requires both fairness and functional accuracy, and achieving either requires evaluation frameworks that reflect local contexts. Samiksha demonstrates that locally-grounded evaluation is both feasible and produces better outcomes.

For a woman in Delhi asking how to stay safe, that difference could be everything.

This is great work. I'll likely be at the Impact Summit as well. Would love to discuss doing something like this in Bhutan; we've been working with the government there, as well as with the new city project, Gelephu Mindfulness City, which just established its legal code and will be an interesting place to do work like this. They are in the process of setting up their institutions, so it's a rare chance to implement tools like this in a new environment.

This is great work, thank you. I am building an AI platfom for teachers to support students with special educational needs and we have ~2000 schools using the platform around the world (https://app.chalklearning.io/). I have been following your work for a while and would be interested to help our teachers and educators build evals from the ground-up. Wondering if there's a way to work with you on this? We can also just use your wevals framework as well.