Community Models

Giving communities the ability to shape AI model behavior.

CIP is working to bring more people into steering the trajectory of AI and its transformative impacts. AI is and will be used to provide information, allocate resources, and make consequential decisions at scale. People should be able to shape this technology, but coordinating community input into complex AI systems is technically and practically hard.

For democratic AI to be anything more than a talking point, we need practical, real-world processes that allow people to define the rules and goals of AI systems in accordance with their values. One of our earliest efforts was Collective Constitutional AI, in partnership with Anthropic, in which we ran a deliberative process among a representative sample of the U.S public to fine-tune their Claude model on a set of collectively-defined principles for AI. You can see coverage of its impacts here, here, and here.

While that project was tied to a closed model, the approach could work for any open-source model. So, over the past year we prototyped a replicable framework, Community Models, for any group to shape an AI model through the constitutional process.

The Community Models Framework

Community Models is built on three core components:

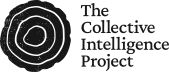

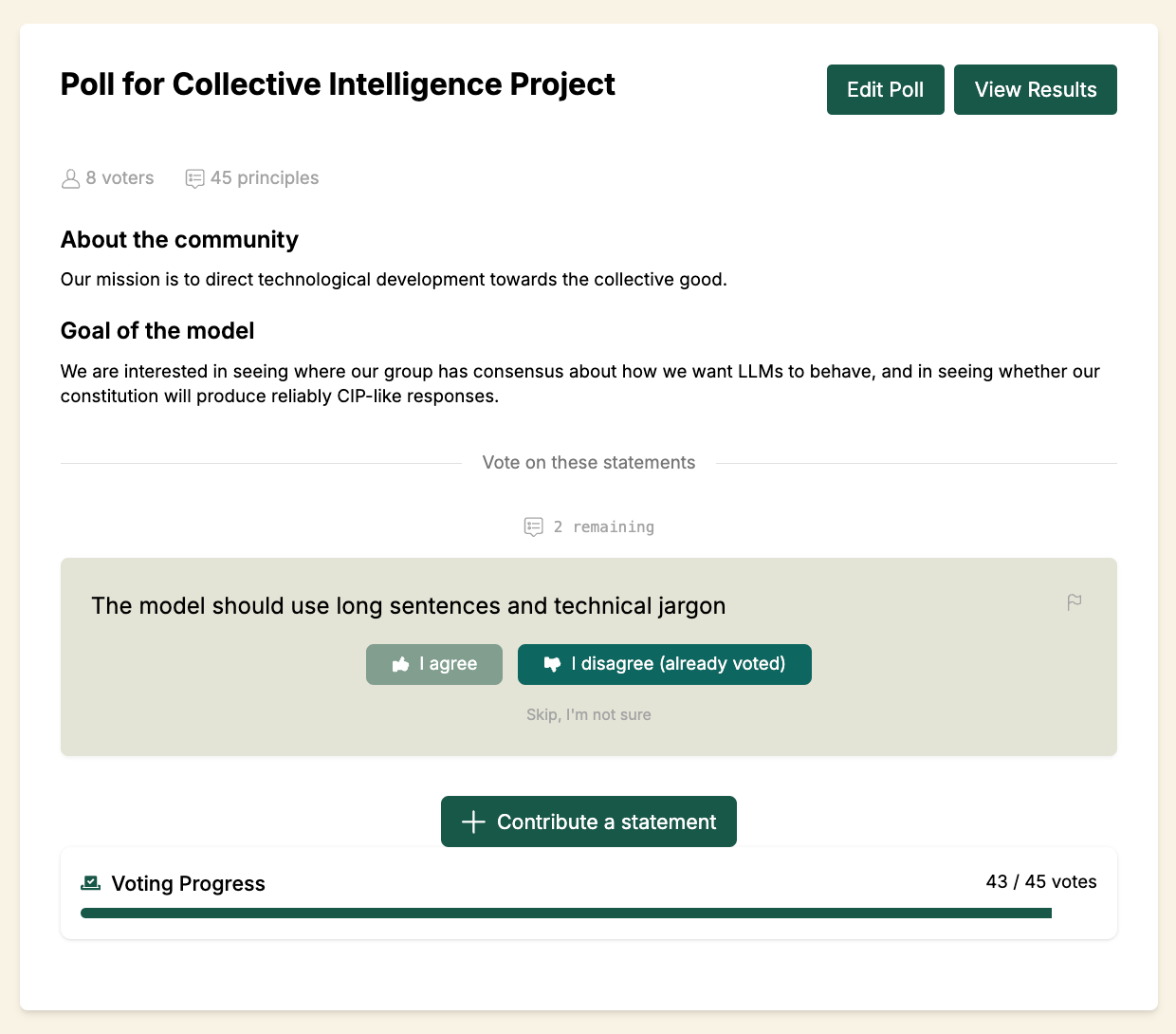

The Collective Constitution Creator is a web-based tool where communities collaboratively build their own constitution through deliberative polls using pol.is. Members propose principles for the AI (e.g., “The AI should understand and respect local cultural norms”), and members vote on principles submitted by their peers.

The Group-Aware Consensus (GAC) Method prevents the tyranny of the majority. Rather than simple majority rule where 51% overrules 49%, GAC first identifies distinct opinion groups within the community based on voting patterns, then only includes principles that have high support across every group. A statement that one group strongly dissents from will fail, even if most others support it. This ensures the final constitution is broadly supported, not just backed by the largest faction.

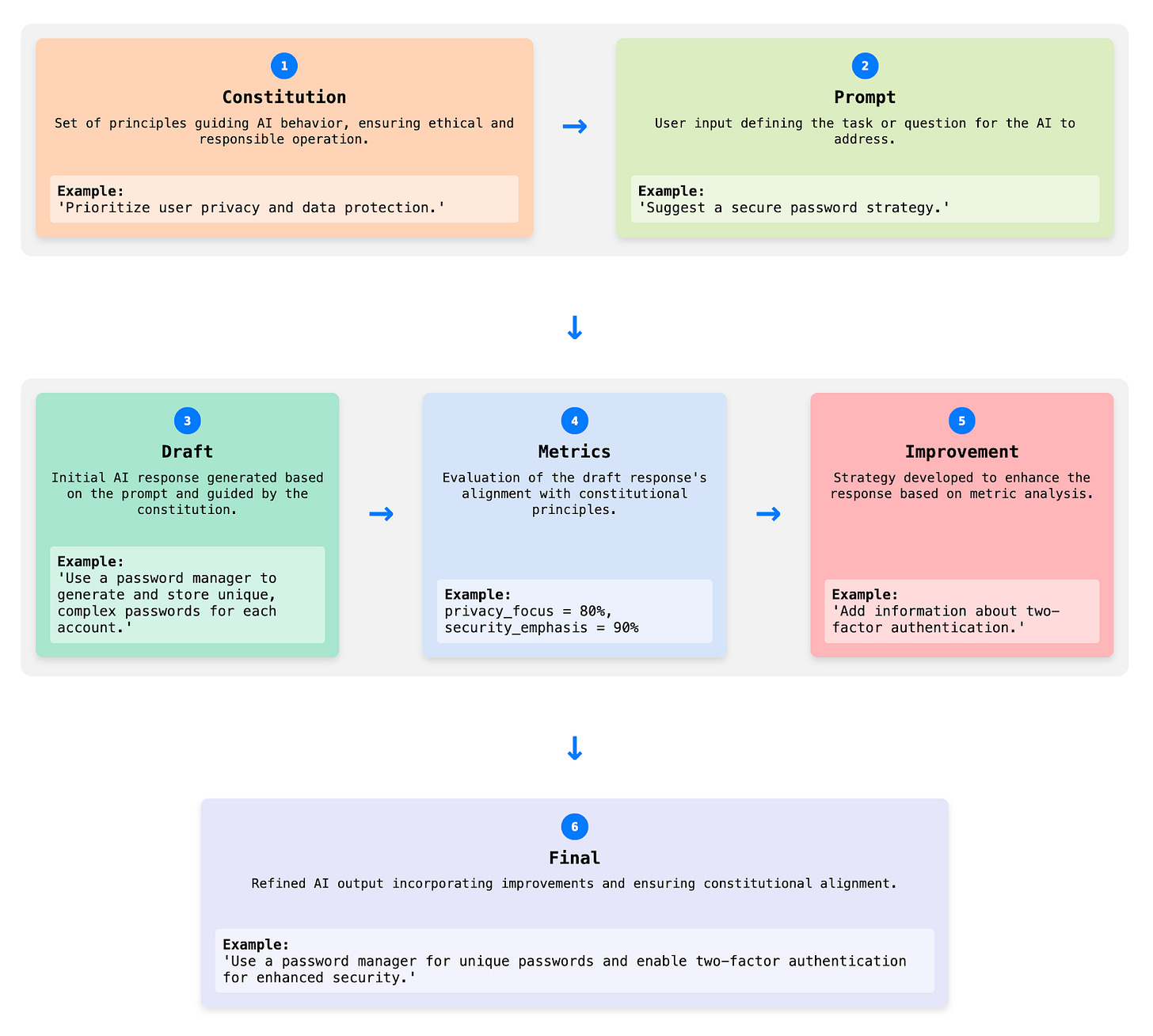

Community Model Shaping uses this constitution to guide model behavior through a multi-step inference process. For every user query, the AI: (1) analyzes the question against the community’s constitution, (2) generates a draft response, (3) evaluates that draft against constitutional principles, and (4) refines the response before presenting it to the user.

Putting the Framework to the Test

We deployed this framework with a range of partner communities, but will focus on three below.

Sri Lankan journalists covering technology policy wanted a model fluent in Sinhala, Tamil, and English that could explain AI policy implications across different sectors of Sri Lankan society. Their constitution emphasized local government literacy, data protection aligned with Sri Lankan law, and the ability to explain complex tech concepts using local examples.

Nigerian digital influencers sought an AI assistant to help navigate ethical boundaries around data privacy, misinformation, and cultural respect. They wanted a model that would flag potential ethical red lines, respect Nigeria’s diverse cultural and religious norms, and recommend local, community-driven solutions before suggesting external interventions.

Second Life Project, a community centered around people re-entering society after long-term incarceration, needed a safe space for questions they couldn’t ask elsewhere. Therapists employed by parole departments can relay conversations to parole agents, and standard advice often puts formerly incarcerated people at risk. Their constitution emphasized trauma-informed approaches for post-incarceration syndrome, awareness of parole officer dynamics, and always prioritizing legal counsel over parole officer contact.

What we learned

All three communities successfully completed the constitutional process and deployed models shaped by their values. However, the same people often didn’t up end using the models that much.

We should focus on cases where decisions affect communities, not individuals.

First, we had asked communities to shape models for personal AI chatbots, which individuals use for their own tasks. In this context, anyone can prompt their way to what they need from the chatbot, as frontier models are increasingly adept at aligning to individual users and their needs.

In our experiments, collective governance was most useful not for personal assistants, but for systems operating at institutional scale, where no single individual can control the outcome:

A school district rolling out AI tutoring systems for thousands of students

A hospital implementing AI-assisted triage protocols

A state court adopting legal AI tools to manage caseloads

In these contexts you can’t simply prompt your way to better results, as you’re subject to the system’s rules and governance frameworks that shape the patterns of interactions of AI agents and real-world systems. This is where community governance is vital, and where the Community Models framework could be deployed. Systems where decisions affect a defined community, individual control is impossible, and democratic legitimacy matters.

We should solve for distribution first.

Our first finding led directly to our second. Despite the groups’ enthusiasm for creating their constitutions, there was limited ongoing use of the resulting chatbot models. The gap between participation in the constitution process and adoption of the chatbot was a valuable lesson, and reinforced our insight that the right context matters for collective governance.

After analyzing our observations and conversations with the communities, we identified a few other key factors.

People often come up with abstract values before concrete needs.

It’s simple to agree on broad ideas like “be fair” or “be respectful.” But it’s a lot harder to define what exactly that looks like in an AI’s behavior, or where current models fall short.

Most people use AI alone.

The idea of a model shaped by the community sounds great, until it feels less useful than just prompting ChatGPT for whatever’s on your mind at the moment.

This tracks with a classic finding from technology acceptance research: “perceived usefulness” is the strongest predictor of adoption. Just building a democratic process isn’t enough. The tool must provide clear, tangible value; and it must be accompanied with a clear plan for distribution.

The Case for Collective Intelligence

As AI systems become more complex and integrated into society, especially in a world where many AI agents will interact across institutional, commercial, and civic settings, one impulse is to centralize decision-making. It’s an understandable impulse; managing collective deliberation is difficult. The risk is gradual disempowerment, where we come to believe that public input is simply “too hard” for complex systems, and we forgo the diverse perspectives needed for healthy societies.

This is why this line of work is so important.

The Community Models demonstrated that it is possible for non-expert groups to provide diverse inputs on complex AI guidelines. Their input was essential in identifying needs (like prioritizing legal counsel over parole officers) that outside expert panels were unlikely to find.

It shows that AI technology doesn’t just have to be the subject of governance; it can also be the tool of governance.

Building On Our Work

Since the Community Models project is open-source, we hope others will experiment with this approach in many different ways.

All code and information can be found at https://github.com/collect-intel/osccai, and the working prototype we built for personal assistants can be found at cm.cip.org.

Some additional paths forward might include:

Identifying concrete failure modes. Rather than starting with abstract values, begin with specific scenarios where existing models fail. What prompts does ChatGPT consistently get wrong for your community?

Creating comparative demonstrations. Build side-by-side comparisons to show how community-aligned models perform better on specific tasks.

Focusing on pain points, not principles. Use constitutional development to address specific, articulated problems of collective governance rather than abstract values.

In all, the Community Models framework offered a glimpse of democratic AI solutions that are genuinely useful, practical, and used to govern systems.

This is helpful as we think about how schools with different regulations and cultures can adapt, align, and audit the AI they use for education. Students and teachers will be the primary individual users, but there are many stakeholders with a voice in shaping its behavior.

Here is the general idea: https://home.xtramath.org/blog/xtramath-ai-building-public-infrastructure-for-universal-math-fluency

Thanks so much for this. Your work is very inspiring. We would love to help contribute to this and will take a look at the github.